Did Al Bano and Romina Power Pioneer Hyperpop?

An overview of Al Bano and Romina Power’s repertoire, between kitsch and innovation

This is the first installment of “beyond la dolce vita,” a summer series where we take the most overly-sentimental and stereotypical Italian songs and singers (you know the ones) and make a case for their artistic merit, beyond their most mainstream success.

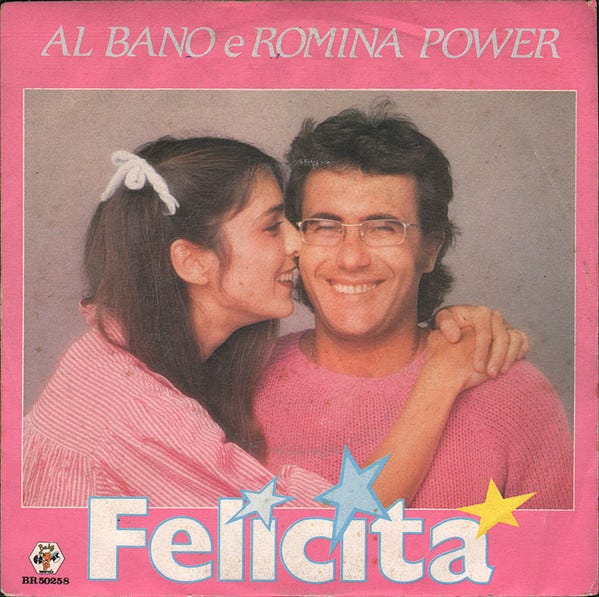

Around the world, “Felicità” by Al Bano and Romina is, on a par with “Sarà perché ti amo,” the quintessential Italian sound. The rich orchestration (synth-heavy, but still prevalent), the lyrics that describe what happiness is (holding hands, going far, a down pillow, the rain outside your window, among other things) in a way that is reminiscent of “My Favorite Things” from The Sound of Music, all tied together with the contrasting yet complementary vocals of the duo, effectively sell an image of Italy that’s all sunshine, love, and happiness.

This post would not be possible without Demented Burrocacao’s essay “Al Bano e Romina Power Effetto Amore,” which appears in the book Italian Futuribili. We quote him and attribute the quotes to him when applicable.

Upon superficial listening, Al Bano and Romina were indeed ambassadors of Italian conservative melodic pop abroad, but the truth is, they synthesized a series of influences that they then masked as earworm-like tracks. To detractors, these repertory-wide tropes are quite corny and kitsch, but if you listen closely to their songs, you’ll realize that they devised a vision of pop that was over the top, self-referential, made of pure artifice, and unafraid of kitsch—qualities that could grant them timelessness in what became a cookie-cutter cultural landscape. Could it, indeed, be an early version of hyperpop?

Coming from farmer stock, “Al Bano was a working-class hero, who found fame after a series of menial jobs thanks to a voice perfectly primed for Italian melodies mixed with a hint of soul music,” writes Demented Burrocacao in Italian Futuribili. “She was a gorgeous girl with Hollywood pedigree, used to consuming LSD and with a passion for hippie aesthetics and song-writerly country music, and a light but harmonious voice.”

They met in 1967, when she was sixteen and they were both starring in the movie Nel sole, with roles that mimic their real-life counterparts: Al Bano played the broke student Carlo, while Power was the high-born Lorena, and they eventually fall in love.

Their first artistic collaborations date back to 1969 and include the chorus part of “Acqua di mare” and, in 1970, “Storia di due innamorati.” Still, in the early 1970s, they mostly performed and acted separately. Notably, she had a role in Jess Franco’s Marquis de Sade: Justine, with Klaus Kinski playing the lead role. During these years, Al Bano worked with Mikis Theodorakis on a piece about the military dictatorship in Greece and wrote pieces for Giuni Russo. Prior to meeting Al Bano, Romina had indulged in erotic films and in weird, psychedelic-lite folk with the album Ascolta, ti racconto un amore (1974), which was offset by her ingénue demeanor.

They formally kicked off their artistic partnership in 1974 by establishing the record label Libra. Once they got together both artistically and romantically, they began singing of love—an abstract love where, at first glance, everything is perfect in a saccharine, almost sterile manner. Explicit outliers from their 1975 album Atto I include “Realtà ed evasione,” which dabbles in symphonic krautrock, and soft psychedelic folk in “Moderno Don Chisciotte,” “Se ti raccontassi,” and “Sensazione meravigliosa.”

“Atto I is a disquieting record, almost morbid in that this husband and wife duo reveal their own weaknesses in a way that still has shards of human elements versus the glossy relationship they would portray in the 1980s. These underlying contradictions between sin and redemption make them believable in an alt context,” reflects Demented Burrocacao.

In 1976, they participated in the Eurovision Song Contest with “We’ll Live It All Again.” As we mentioned in our previous post on Italian Eurovision entries in the 1970s: “Even though Power was just 24 in 1976, in the lyrics, she reminisces with a longtime lover on the good times past, with the promise to live it all again. The melody bears an uncanny resemblance to Frank and Nancy Sinatra’s version of ‘Something Stupid.’”

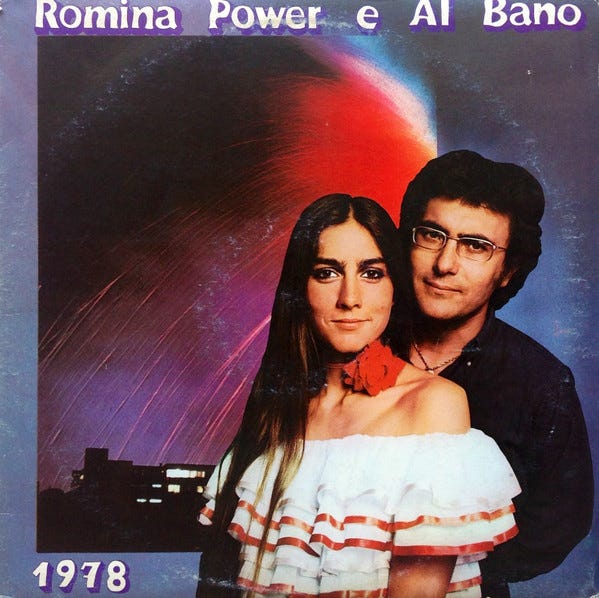

After the disco interludes of the 1978 album 1978 (yes, that’s the title), and the proto-Italo-disco track “U.S. America,” they find their treacly, dolce-vita formula in 1982. Enter “Tu soltanto tu” and, most importantly, “Felicità.”

“Felicità” and its namesake album, known in Italy as Aria pura (1982) has a stacked cast: the arranger is Gian Piero Reverberi, the creator of disco/baroque/classical-crossover act Rondò Veneziano; other collaborators include Cedric Beatty (he worked with Dada, Den Harrow, and Gong), Mats Björklund, and Geoff Bastow. “This track portrays happiness as if happiness were complete automation, with hints of socialist realism,” writes Demented Burrocacao. In it, you hear both mandolins and Computer Love by Kraftwerk. Even the vintage-like “Sharazan” basks in an unreal glow.

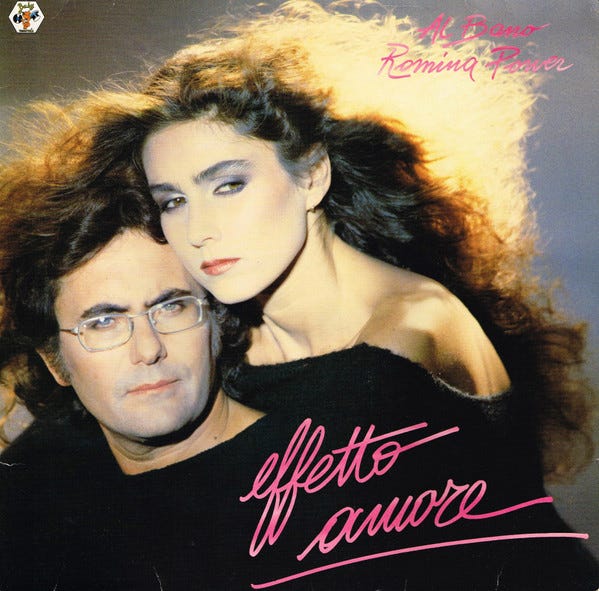

The 1984 album Effetto amore turns them into androids. On the album cover, they share the same styling, down to the makeup. “Al ritmo di beguine” starts as a ballad, but has a video-game-music-like arrangement—think Starship’s “Nothing’s Gonna Stop Us Now.” In this album, Italian melodic pop, Vangelis-style anthems, and proto-dance tracks coexist, in songs like “Ci sarà,” “Grazie,” and “Un’isola nella città.”

Ultimately, whether or not this feelings-porn and sentimental overload does anticipate genres like hyperpop, the truth is that—refinement aside—they have had tremendous commercial success in continental Europe, the former Soviet Union, and Latin America. And their schmaltzy sound does act as a gateway to the myriads of innovations in 1970s and 1980s Italian music. Chances are that, if you are not from Italy and you are here, Al Bano and Romina have been the first Italian-language artists you were exposed to.

Great essay. Felicita is a prime example of Italian pop at its best. I remember that the song was unstoppable throughout Europe during the summer of 1982. Greek radio couldn’t get enough of it, and neither could the public, with the LP becoming a smash hit. (It also included the very popular and very silly Ballo del Qua Qua by Romina, which is basically a vocal version of the Birdie Song/Birdie Dance).