Beyond Gender, Beyond Genre

Ivan Cattaneo’s punk-electro-futurist provocations turned Italian pop into a medium of queer expression and cultural subversion.

In the landscape of Italian pop culture, Ivan Cattaneo remains an outlier, someone whose work, presence, and persona constantly eluded definition. Long before terms like queer or gender-fluid entered the mainstream vocabulary, Cattaneo was embodying all of it: flamboyant, intellectual, erotic, irreverent, and above all, fiercely original. Musician, songwriter, visual artist, performer, and provocateur, he moved through the 1970s and 80s with a clarity of vision that often left audiences and critics scrambling to catch up.

Speaking today with disarming lucidity, Cattaneo is both amused and vindicated by the resurgence of interest in his work among younger audiences. “Everyone thought I was crazy,” he says. “Now they say I was ahead of my time. Finally.”

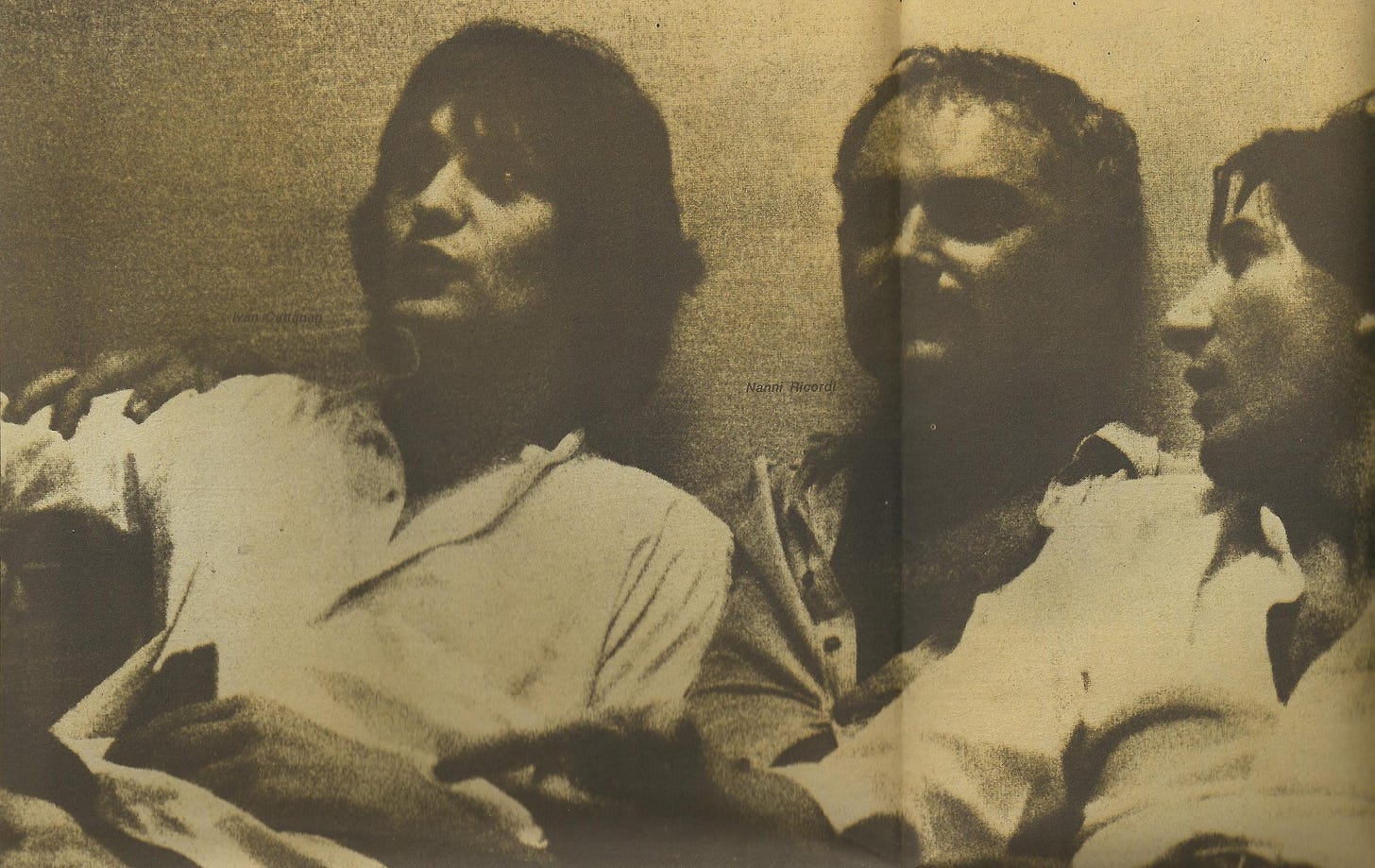

That work spans a career shaped as much by Milan’s Brera Academy as by the post-glam undercurrents of early 1970s London. After a formative period in the UK, where David Bowie, Eno, and a still-underground queer nightlife left a deep imprint, he returned to Italy by accident, dodging military service thanks to a “psychological incompatibility” declaration furnished by a friend. The timing was fortuitous. He started doing small music performances organized by the underground magazine Re Nudo; during one of these, he caught the attention of Nanni Ricordi, who offered him a deal with the radical label Ultima Spiaggia.

His early albums, especially U.O.A.E.I. and Primo Secondo e Frutta (Ivan compreso), stood in stark contrast to the rigid expectations of Italian pop. He wasn’t interested in hits. Ivan was inventing a language: an irreverent, genreless mix of poetic nonsense, performance art, glam rock, and dadaist theater. But it was with Superivan in 1979 that Cattaneo began crafting a pop persona as sharp as it was subversive. With Roberto Colombo as producer and collaborators like Premiata Forneria Marconi musicians in the studio, he refined his sound into something more playful yet musically precise. The album’s visual identity, a photomontage of Ivan’s face on a bodybuilder’s torso, signaled a new phase: homoerotic, synthetic, and defiantly camp.

“People today have brands and stylists,” he says. “Back then, I had nothing but instinct and courage. I was throwing myself into the storm.”

He exercised total control over his output, writing his own lyrics, designing his album covers, styling himself for television appearances, and even directing set designs for cult TV shows like Mister Fantasy. It wasn’t about spectacle for spectacle’s sake. It was about authorship. “I never saw myself as just a singer,” he explains. “I was always an artist, someone who created entire worlds.”

Urlo di una spia in agguato (Avant la guerre), released in 1980, wasn’t just radical in sound, it was a visual manifesto. Designed with Studio 3040, the fold-out cover unfolds like a surrealist collage, with Cattaneo’s face split, mirrored, and layered in bold hues and cryptic iconography. The fragmentation of identity on the cover echoes the themes of sexual fluidity explored in the album’s standout track Polisex, a prophetic celebration of non-binary desire long before the language existed to define it. The title stretches across the panels like a secret message, anchoring an album where music, image, and ideology merge into one unclassifiable whole.