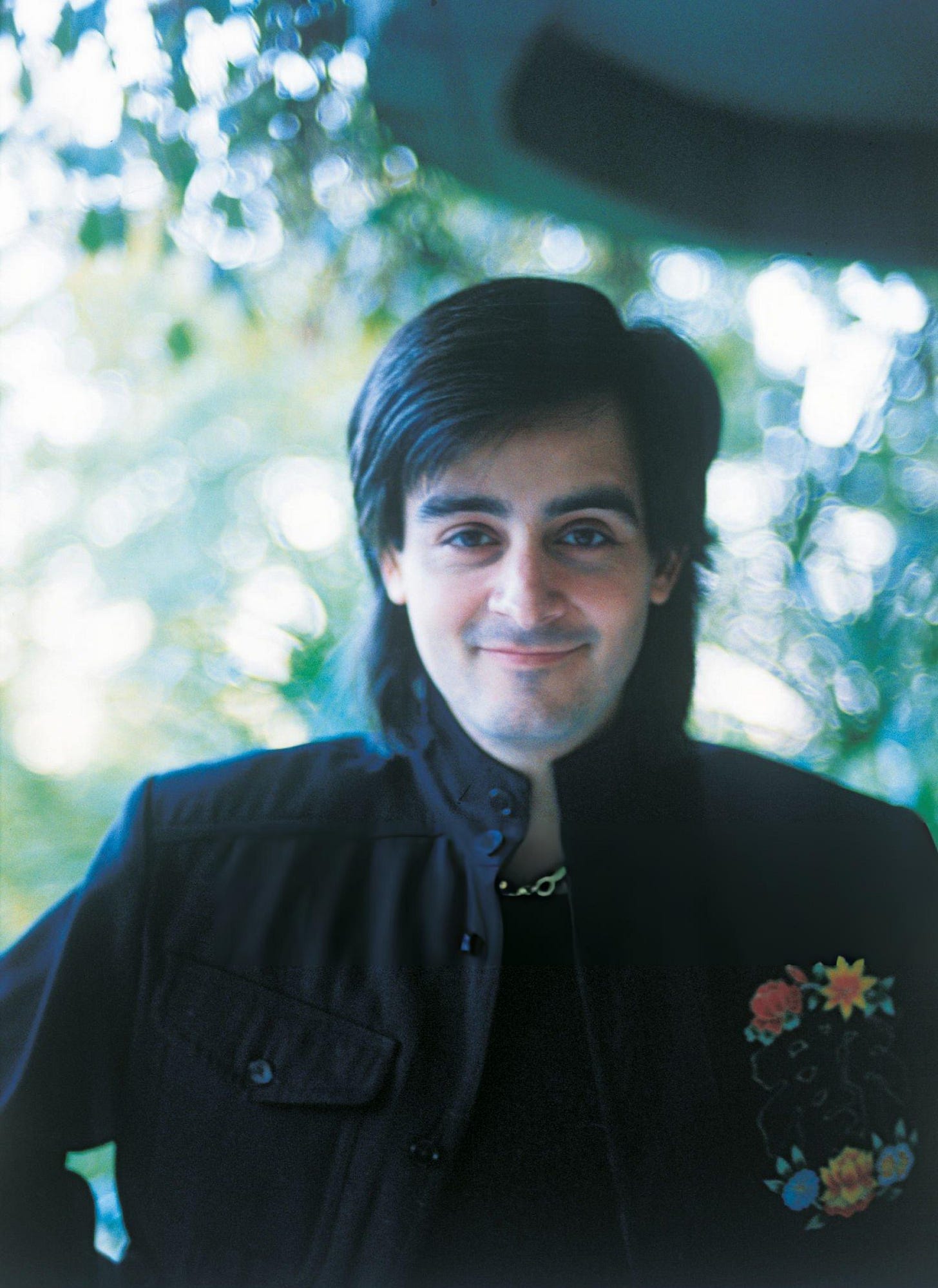

Between Prog, Giallo, and Disco: Our Interview with Claudio Simonetti.

How the composer, arranger, and producer brought Italian disco to global charts.

Claudio Simonetti achieved cult status in genre entertainment because of the movie soundtracks he penned for some of the most prominent Italian Giallo films: Profondo Rosso (1975) celebrating its 50th anniversary, came with a soundtrack that effortlessly elevated typical “spooky” soundbites with prog influences; Tenebrae (1982) combines horror hints with synths and electronic stylistic flourishes. Demons (1985) added tribal beats, while Phenomena, of the same year, mixed electronic instrumentation with operatic vocals.

He is also one of the most influential composers, arrangers, and producers of disco music in Italy.

The son of composer Enrico Simonetti, the Brazilian-born Claudio started playing the piano at age 8. “I then started studying at the Conservatory, specializing in piano and composition, but in parallel to that, I was active in various rock bands, all the way to Goblin,” he tells us. “Then, we split after 1978, because the prog era was over, and in came this dance and electronic-disco music era. Since I really liked this new genre, I just started being active in that scene.” To this day, he has dance music in his earbuds in his day-to-day life.

He attributes his love for dance to his Brazilian roots. “Rhythm is in my blood, so the 4/4 beat brought me back to my roots.”

Upon his pivot to disco, he and record producer and entrepreneur Giancarlo Meo worked on their label Banana Records, which Meo already had and which Simonetti joined as a partner. “In the late 1970s, the big Italian record labels did not believe in disco music,” Simonetti recalls. “I was one of the first disco-music producers and composers in Italy and we would pitch projects to big record labels,” he explains. “executives would say leave this stuff to the Americans.” Their successes proved them wrong, and, since they already had their own label, they no longer needed backing from the majors.

His project Vivien Vee actually charted in the United States with “Give Me a Break.” “She was both the face and the voice of the act,” Simonetti specifies. “Sure, singing was challenging, but mainly because she could not speak English. Actually, when we came to America to promote her, we created a whole mystique about her being unwilling to do interviews. The truth was that she would not be able to conduct the interview because she was not fluent in English.” This was hardly an exception in that era. “Raffaella Carrà was the exception: she could basically speak any language,” says Simonetti, remembering her fondly.

Another one of his creations, Easy Going was actually a living documentation of the way disco and club music was evolving at that time, especially regarding the juxtaposition of the more Soul-inspired sounds from America and the electronic beats from Continental Europe. “Baby I Love You,” from 1978, combines the feel of Saturday Night fever with electronic vocal distortions, while he 1979 track “Fear” starts in Moroderian fashion, a symphonic poem of cyberpunk dystopia, only to then give way to strings, similar to what Amanda Lear accomplished with “Follow Me” in 1978. “A Gay Time Latin Lover,” from 1980, is almost retro in its orchestration.