Matia Bazar Pioneered Future Nostalgia

How the juxtaposition of operatic vocals and electronic instruments created their emblematic sound

Italian band Matia Bazar defined the soundscape of the mid 1980s thanks to a combination of electronic music, lush synths, and the vocal range of the lead singer Antonella Ruggiero, an agile soprano who could easily pull off pop, gospel, jazz, disco, and contemporary sounds.

The changing formations over the years also contributed to the band’s ever-evolving style and genre.The original formation had all the instrumentalists, Carlo Marrale (voice and guitar), Piero Cassano (keys and voice) and Aldo Stellita (bass and chorus) come from the band Jets. When Cassano left in 1981, Mauro Sabbione took over temporarily, only to make room for composer and keyboardist Sergio Cossu, a pioneer in the usage of the MIDI protocol.

Established in Genoa in 1975, Matia Bazar were known for experimenting even in their earlier work, which some deemed textbook-Italian pop that then veered into rock. Their 1976 track “Limerick” contains traces of proto disco, while their 1977 Sanremo entry “Ma perché” and “Gran bazar” are pure dancefloor hits. Their Eurovision entry “Raggio di Luna” might have a nostalgic vibe at first, but a closer listening will definitely lead you to perceive it as a precedent to the future nostalgia they developed in the mid 1980s. Below, we highlight their three seminal 1980s albums.

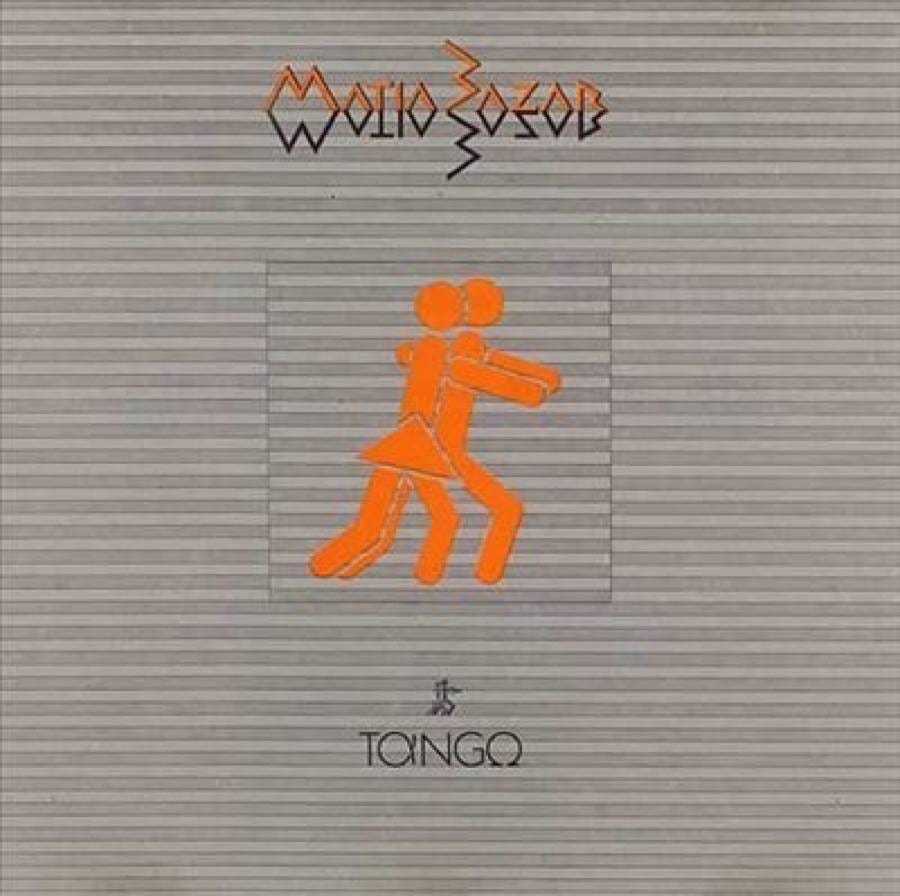

Tango (1983)

Tango is the synthesis between melody and technology. The lead single “Vacanze Romane,” their Sanremo entry for 1983, perfectly combines retrofuturism and nostalgia, both via the imagery it describes, the sound, and the lush use of synths. It was disruptive in that it united a classically-trained voice such as Antonella Ruggiero’s with the electronic arrangements of Mario Sabbione’s keys. Its lyrics cite a Roman Holiday, La dolce vita, The Merry Widow and Carlo Lombardo’s Il paese dei campanelli, and evoke a past grandeur of the city. “Despite being composed of micro-plagiarisms of songs from the 1920s and 1930s, it has the vigor of a total work of art,” writes the music critic Demented Burrocacao in Italian futuribili.

Interestingly, their original choice for Sanremo was the track “Palestina,” which combines Middle-Eastern influences with electronica, and which Ruggiero used to perform live alternating raising her fist and outstretching her arm in a Roman salute.

And while “Scacco un po’ matto,” and its vocoder that splits Ruggiero’s voice is pure Europop, “Elettrochoc” anticipates both techno and intelligent dance music: its seemingly delirious lyrics, conveyed by four characters suffering from various mental-health conditions, condemn electro-convulsive therapy.

The title track “Tango nel fango,” uses the dance styles such as tango and milonga as verbs as a way to portray a self-contained seduction. It’s a markedly retro track, almost like a merry-go-round tune.

From a visual-culture perspective, “Il Video Sono Io” yielded a meta-commentary-like and genre-defining music video, which appears explicitly postmodern “in its attitude towards design, its use of colours, the reflexion on the possibilities and the nature of television,” as stated by Bruno di Marino in the essay “Pride and Prejudice”. A Brief History of the Italian Music Video

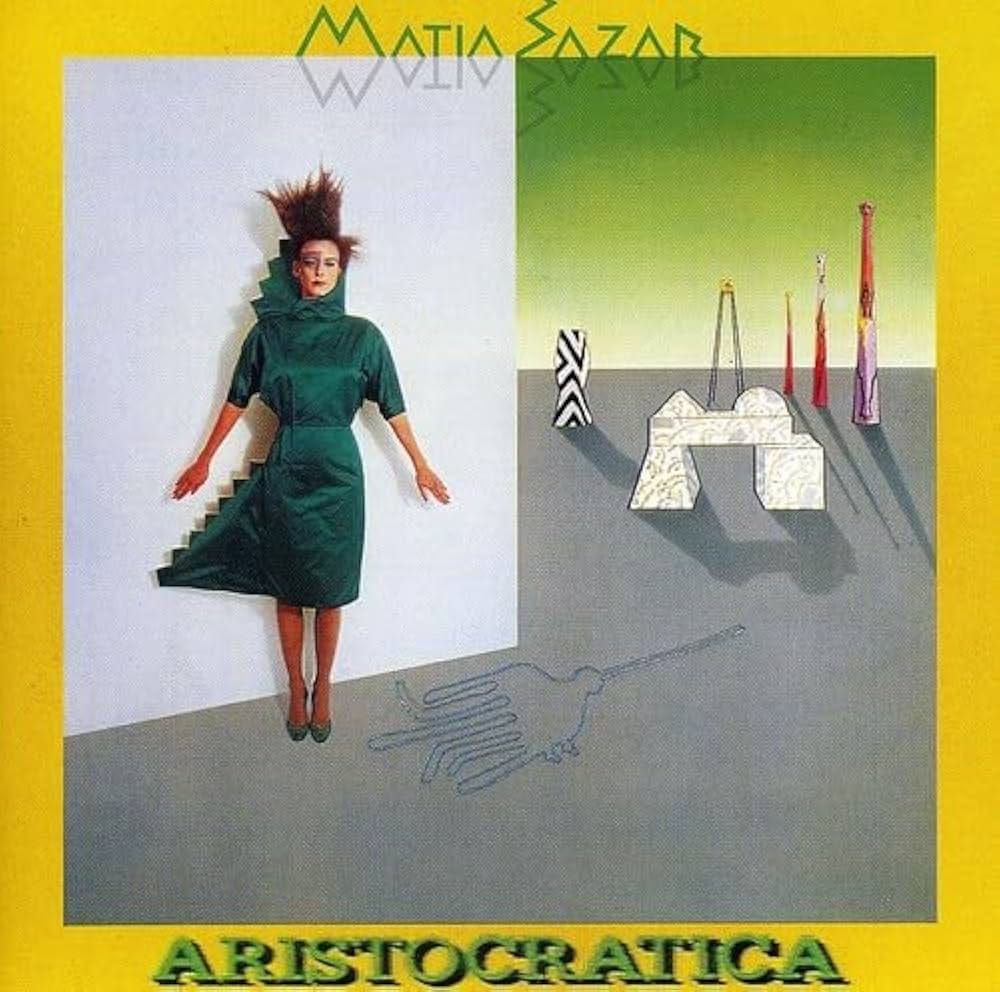

Aristocratica (1984)

Released in 1984 Aristocratica dials up experimentation. Tango is still indebted to the Italian music tradition (melodies you can sing, lyrics that are not too cryptic and fairly easy to remember), while Aristocratica is fully projected into the future. It also marks the entrance of Sergio Cossu as a session player. The lyrics are nothing short of cryptic, the arrangements can easily be labelled as proto techno, and experimentation is just free flowing. The band brought to life an extraordinary album that was both innovative and prophetic, blending music, art, technology, and design